Joint and Ligament Tears

JOINT DISEASE, DIAGNOSIS, MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

A common cause of lameness in our pets involves damage or disease to joints. Structures involved with joint disease include bone, cartilage, ligaments, muscle, and tendons. Joint disease can be developmental (occurring during growth), degenerative (wear and tear) or traumatic and, as such, affect all ages and breeds. Examples of common joint disease include cruciate ligament tears, dislocations, bone, and cartilage fragmentation and arthritis. Depending upon the cause of joint disease, treatment may be medical, surgical, and regenerative (stem cell, platelet-rich plasma: PRP).

DIAGNOSIS

First, we obtain a detailed history of your pet’s condition. Some things are more evident than others – such as traumatic injuries versus slow onset degenerative or infectious causes. A physical examination will often lead to a diagnosis since joint pain and instability are palpable, and our pets often react to manipulation of the affected joint.

Other diagnostic tools that aid in diagnosis include x-rays, ultrasound, CT, MRI, arthroscopic evaluation, and joint fluid evaluation. There are also infectious causes such as Lyme disease that require blood tests.

After a complete history and examination, we discuss and recommend which diagnostics are best suited for your pet’s condition.

At the Animal Clinic of Billings and Animal Surgery Clinic, we have access to the latest state of the art MRI and CT machines we use frequently on our veterinary patients in need of advanced MRI and CT special diagnostic imaging.

TREATMENT

Based on the examination and diagnostic results, your veterinarian will develop a treatment plan. Some conditions such as arthritis are progressive, and treatment is aimed at relieving pain and in amelioration as well as slowing the progression of the disease. Several oral and injectable medications can significantly improve your pet’s comfort and allow for maximal mobility. A newer treatment modality in the treatment of joint disease involves the use of stem cells and PRP, which uses cells harvested from your pet’s blood, tissue, and bone marrow to help heal diseased tissue in joints, muscles and tendons.

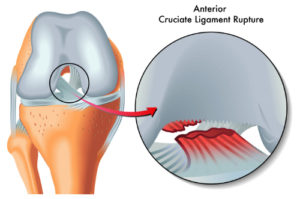

Some joint diseases require surgery to repair or remove damaged tissue and return the joint to a normal range of motion and function. Examples include cruciate ligament tears (similar to ACL injuries in people) which, in dogs, can be traumatic or degenerative; and osteochondrosis dissecans (OCD), which is developmental and involves cartilage that is often loose or floating in a joint, causing pain and lameness.

Hip and elbow dysplasia are developmental diseases that quickly lead to permanent arthritic changes in the joint. These types of joint diseases are treated surgically. Minimally invasive techniques such as arthroscopy can often be used. Arthroscopic surgery involves the placement of a small camera into the joint to evaluate and treat disease through tiny incisions, making recovery from surgery easier on the pet. Your veterinarian will help guide you to determine which type of medical or surgical intervention is most appropriate for your pet.

RECOVERY

It is important for pet owners to understand the recovery and healing process following joint treatment or surgery. Many procedures depend on bone healing, which, in healthy adult pets, generally takes anywhere from 8-12 weeks. Successful treatment of joint diseases is a team effort involving you and your veterinarian working together to rehabilitate your pet.

At the Animal Clinic of Billings/Animal Surgery Clinic, we often prescribe a post-operative rehabilitation plan that gradually increases your pets’ activity as they heal in order to get them back to athletic function.

Let our highly trained and experienced team of veterinarians and veterinary technicians help you keep your pet as happy and healthy as they can be.

Call the Animal Clinic of Billings to schedule your pets next wellness examination with us today!

406-252-9499 REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT

ACL AND CRCL (CCL) EXTRA CAPSULAR REPAIR

CRANIAL CRUCIATE LIGAMENT (CRCL OR CCL) AND ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT (ACL) DISEASE IN DOGS

What is the cranial cruciate ligament?

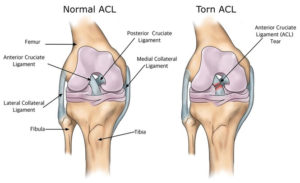

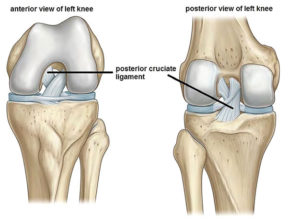

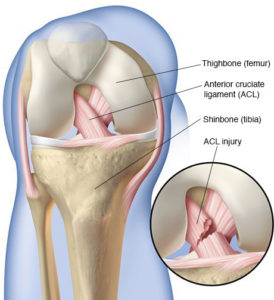

In dogs, the cranial cruciate ligament (CrCL or CCL) is the same as the “anterior” cruciate ligament (ACL) in humans. A ligament is a connective or fibrous band of very tough tissue that connects cartilage or two bones together at a joint. The cranial cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL) connects the thigh bone with the lower leg bone and acts to stabilize the stifle joint, as well as prevent it from over-extending or rotating. The stifle joint is the joint located between a dog’s thigh bone, or it’s femur, and the two shin bones or it’s tibia and fibula. In essence, the stifle joint is the quadruped equivalent of a human knee.

The tearing of an ALC in humans is quite common, especially among athletes and during sporting activities such as skiing, football, and golf, etc. However, cranial cruciate ligament disease affects dogs very differently than it does ourselves. Most human ACL injuries happen suddenly where an otherwise healthy ligament gets traumatically twisted and snaps in an instant. With dogs, the CCL or CrCL typically degenerates slowly over time, much like a rope begins to deteriorate and frays after it’s left out in the sun for several years. For this reason, treatment and medical management for a dog with a CCL or CrCL injury or disease is approached quite differently than a human doctor would treat the equivalent ACL injury in one of us.

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is the sudden failure of the ligament, which renders complete and partial instability of a dogs stifle joint. Cranial cruciate (CCL or CrCL) ruptures are when the cranial cruciate ligament becomes torn. A torn or ruptured CCL or CrCL is the most common cause of rear leg lameness in dogs. Ruptured and torn CCL’s or CrCL’s are also major contributors to degenerative joint disease within the stifle joint in dogs.

From a preventative standpoint, understanding your dog’s genetics may be necessary for restraining stifle deficiencies and knowing which activities your dog should avoid. This is not always easy to predict or understand, but what we do know is all breeds are susceptible to a ruptured CCL or CrCL and stifle joint disease. We do not know the exact cause of this, but genetic factors are likely the most important. Certain breeds are predisposed to others. Most notably, Labradors, Rottweilers, Boxers, Newfoundlands and West Highland White Terriers less than four years old. Beyond that, all other dog breeds older than five years old, spayed female dogs over five years old, and large-breed dogs between one to two years old are the next most likely candidates.

How can I tell if my dog has cranial cruciate ligament disease?

Limping will likely be the first sign that your dog has sustained a CCL or CrCL injury. This could happen out of the blue, after or during exercise activity, or even surface sporadically at random. The severity of a CCL rupture is dependent on whether it’s been partially torn or completely torn. The severity of a CCL or CrCL rupture is also indicative of the duration of time in which it took to become ruptured, meaning whether it happened suddenly, or has been degenerating over a long-term period of time. In severe cases, a dog may have incurred simultaneous cruciate injuries in both knees and not have the ability to get up on their own at all.

If the CCL or CrCL rupture takes place suddenly, the injury will result in non-weight bearing lameness and fluid build-up in the joint. Meaning, the dog will not regain the use of its leg until the ruptured tendon has been repaired. A tell-tale indicator of a sudden CCL or CrCL rupture is if your dog is unable to walk on one or both of its legs, and holds the leg up in a partially bent position when standing.

A degenerative CCL rupture or joint disease means the ligament’s structural composition and ability to function normally are steadily declining. You may notice a subtle or occasional lameness in one of your dog’s limbs that could last from weeks to months if this is the case. If your dog shows sudden signs of lameness during regular activity, it could suggest a degenerative rupture or joint disease. Other indicators include a noticeable decrease in muscle mass in one or both of the dog’s rear legs, especially in the quadriceps muscles.

If degenerative joint disease or a degenerative cruciate rupture has taken place, gradual and permanent deterioration will continue to affect your dog’s joint cartilage, the CrCL ligament and all of it’s surrounding muscles if left untreated.

What is my dog experiencing with a ruptured cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL)?

The tearing of a cruciate ligament unleashes a cascade of events that ultimately and unfortunately result in chronic knee pain and rear-limb lameness. Clients often ask us, “when will my dog get osteoarthritis?” Unfortunately, even at the earliest stage of a CCL injury or disease, osteoarthritis has already started.

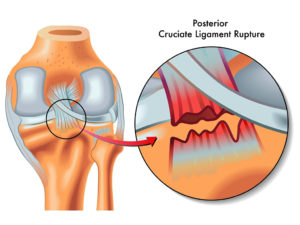

Upon the CCL rupturing completely, the ligament loses mechanical function. Without this fundament support system in place to stabilize the knee, the femur (thigh bone) will roll down the backward slope of the tibia (shin bone) beneath it each time the dog bears weight on the impaired leg. The inherent mechanical lameness that results from this loss of support is swiftly accompanied by pain for the dog.

In some dogs, this mechanical deficiency can result in further damage and trauma to other structures of and within the joint. Most notably, the two adjacent support cartilages we call the menisci. As the femur rolls down the backward slope of the tibia each time the dog bears weight on the impaired leg, it can crush and tear these menisci cartilages.

What caused my dog to rupture it’s cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL)?

The causes of cranial cruciate ligament disease are most frequently caused by repetitive micro-movements to the cranial cruciate ligament. In other words, repeatedly putting strain and pressure on the ligament in the same way. This action causes the ligament to stretch each time pressure is applied, which ultimately weakens the ligament over time and eventually causes it to tear.

The causes of cranial cruciate ligament disease are most frequently caused by repetitive micro-movements to the cranial cruciate ligament. In other words, repeatedly putting strain and pressure on the ligament in the same way. This action causes the ligament to stretch each time pressure is applied, which ultimately weakens the ligament over time and eventually causes it to tear.

In some cases, a dog will be born with abnormalities or conformation that develop during the ligaments growth which can lead to CrCL ruptures as well. If the bones that make up the stifle joint were abnormally formed, the cruciate ligament, in turn, receives abnormal strain and movement whenever the dog walks or runs.

Cruciate ligament deterioration can also be caused by an injury to the stifle joint, athletic exertion, trauma from jumping and landing off-centered, dislocating a kneecap (also known as medial patellar luxation), or any other accident or knee injury that causes the ligament to tear.

Additionally, cruciate ligament disease can result in dogs simply from obesity, as the additional weight carried by the dog increases the amount of strain and pressure applied to the ligament with each repetitive step the dog takes. This is just one more reason why weight control is so important for dogs of all ages and breeds in preventing further health problems. When a dog is overweight or obese, the additional weight forces the dog to walk differently and favor otherwise un-natural movements. This, in turn, increases the force of impact and strain on the cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL) and stifle joint, in addition to every other part of the body, which increases the likelihood of a CCL or stifle injury / deterioration.

How are cruciate ligament ruptures diagnosed in dogs?

If your veterinarian suspects your dog is suffering from a cruciate ligament rupture or stifle joint disease, he or she will have several diagnostic procedures they’ll need to perform to find the source and severity of the injury. A diagnostic evaluation for a cranial cruciate rupture will include a cranial drawer test, which involves the veterinarian using his or her hands to make specific manipulations to the dog’s affected limb. Depending on how the dog’s limb is able to be manipulated, the veterinarian is able to assess the status of the cruciate ligament.

If your veterinarian suspects your dog is suffering from a cruciate ligament rupture or stifle joint disease, he or she will have several diagnostic procedures they’ll need to perform to find the source and severity of the injury. A diagnostic evaluation for a cranial cruciate rupture will include a cranial drawer test, which involves the veterinarian using his or her hands to make specific manipulations to the dog’s affected limb. Depending on how the dog’s limb is able to be manipulated, the veterinarian is able to assess the status of the cruciate ligament.

Because this could cause a great deal of pain to dogs suffering from a torn or ruptured cruciate ligament, anesthesia or sedation is sometimes necessary during a cranial drawer test. A tibial compression test is another form of manual assessment your veterinarian may employ to determine stifle stability. Other tests to evaluate CCL or ACL injury include a tibial thrust test and a stifle hyperextension test which may also be employed at this time.

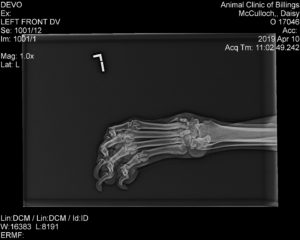

Additionally, X-Rays will need to be taken of the stifle joint to confirm the diagnostic evaluation, and in rare cases, an MRI may be needed as well. In most dogs, a mini arthrotomy or exploratory arthroscopy surgery or, “keyhole surgery,” (probing the affected area with a very small camera inserted through a very small incision) may also be needed to confirm the diagnosis and perform the operative repair.

Additionally, X-Rays will need to be taken of the stifle joint to confirm the diagnostic evaluation, and in rare cases, an MRI may be needed as well. In most dogs, a mini arthrotomy or exploratory arthroscopy surgery or, “keyhole surgery,” (probing the affected area with a very small camera inserted through a very small incision) may also be needed to confirm the diagnosis and perform the operative repair.

Exploratory arthroscopic surgery is a minimally invasive surgical procedure that allows your veterinary surgeon to investigate and repair the inner-most mechanics and insides of joints, bones, cartilage tears, torn ligaments, as well as remove problematic and free-floating bone fragments.

How are cranial cruciate ligament injuries treated in dogs?

All Dogs with a complete or partial CCL tear should be treated with stabilization surgery. Stabilization surgery is recommended for all dogs because it significantly reduces joint degeneration, enhances limb function, has a faster rate of recovery, and has a very good prognosis (as long as it’s performed by a veterinary surgeon experienced in ACL, CCL or CrCL repair surgery).

Dogs that do not receive surgery, on the other hand, have a 20 percent success rate of improving or ever becoming normal with non-surgical approaches to medical management of the condition. Because of this, non-surgical treatment methods are rarely recommended.

Exceptions do occur (seldom), but typically only apply to pets with extremely bad pre-existing medical conditions such as severe heart disease or uncontrollable hormone disorders where the risks of a general anesthetic or surgery are considered too dangerous for dogs suffering from those conditions.

Cranial Cruciate Ligament Surgery for dogs

Canine CCL or CrCL Surgery is categorized into several different techniques. Each treatment method aims to replace the diseased or ruptured ligament by cutting the tibia and re-aligning it in such a way that prevents it from moving and stabilizes the stifle joint to withstand the forces acting over it.

Types of cranial cruciate ligament surgery used on dogs

TIBIAL PLATEAU LEVELING OSTEOTOMY (TPLO)

A TPLO surgery is a procedure where the top portion of the tibia connected to the stifle joint is cut and rotated as much as twenty degrees or more to produce a more level tibial plateau. This change of angle to the top of the tibia prevents the femur from sliding down the back of the tibial plateau when the dog bears weight on its knee, thus negating the need for ACL replacement or stabilization.

The top portion of the tibia bone that’s been cut and rotated is then permanently anchored into place using a bone plate and screws. TPLO surgeries are the most common orthopedic surgery procedures our veterinary surgeons perform at the Animal Clinic of Billings and Animal Surgery Clinic, as TPLO surgeries tend to be extremely successful and produce very fast recovery times.

TIBIAL TUBEROSITY ADVANCEMENT (TTA)

TTA surgery on dogs is similar to TPLO surgery. Like the TPLO, the tibia bone is cut and bone position is altered to make up for the lost CCL or CrCL, but the biomechanics changes possible with the TTA surgery fall short of the versatility of the TPLO surgery. However, in certain select cases, there may be advantages, and since Dr. Sherburne and Dr. Brown perform both procedures, we can recommend the proper procedure to meet the individualized needs of your dog.

In the TTA procedure, a linear cut through the bone is made along the length of the front part of the tibia. The portion of bone that’s been cut is then moved forward, and a specialized bone spacer along with a bone graft is inserted between the portion of tibia bone that’s been cut and the tibia. Once the bone graft and bone spacer are in place, a very specialized metal plate is secured with titanium screws to fasten the three pieces together securely. The patellar tendon remains attached to the tibia which stabilizes the stifle joint and keeps the femur from sliding back and forth.

Once completed, the TPLO and TTA surgeries both serve to neutralize any potential of the femur slipping down the backside slope of the tibia which eliminates the need for a cranial cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL) in order for the knee to function comfortably.

TPLO and TTA surgeries are known for having excellent outcomes. In fact, 90% of dogs that undergo TPLO or TTA surgery regain normal or near-normal athletic function of their leg without any post-operative complications or the need for long-term pain medication.

CCL or CrCL Extra-Capsular repair surgery

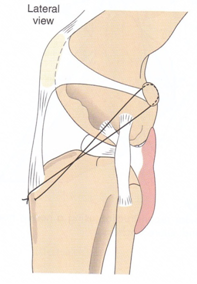

CCL or CrCL extra-capsular repair surgery also called the “fishing line technique,” is a procedure designed to replace the function of a defective CrCL, where a strong suture material is placed along a similar orientation to the original cruciate ligament on the outside of the joint.

The suture acts to stabilize the knee joint until organized scar tissue can form and stabilize the joint on its own. In our experience, smaller dogs and cats are typically the best candidates for this procedure as larger and more active dogs tend to have a much higher failure and complication rate with the extra-capsular repair surgery.

If your veterinarian determines your dog has degenerative abnormalities with genetic origin, it would be wise to avoid breeding your dog as those genetic defects are likely to be passed along to the offspring. A second surgery may be required in 10 to 15 percent of cases, because of subsequent damage to the meniscus (crescent-shaped cartilage located between the femur and tibia in the stifle joint). Regardless of the surgical technique, the success rate is generally better than 85 percent.

What does my dog need after cruciate ligament (CCL or CrCL) surgery?

After cruciate ligament surgery, one of our veterinary surgeons at the Animal Clinic of Billings and Animal Surgery Clinic will design a tailored after-care regiment and physical rehabilitation plan to meet your dog’s individualized recovery needs. Physical rehabilitation therapy (PRT) is essential for patients after surgery to regain muscle memory, strength, and mechanical function of the newly repaired limb or body part.

Our canine physical rehabilitation practitioners are extremely experienced in CCL or CrCL post-surgical management and after-care protocols and are here to help you and your dog through every step of the recovery process. This includes outlining a detailed physiotherapy, hydrotherapy, and laser therapy schedule, as well as designing a custom home exercise plan and timeline for you to follow at home.

Your veterinary orthopedic surgeon will recommend semi-weekly Physical Rehabilitation Therapy (PRT) appointments for your dog during the next two to four months following surgery for optimal post-surgical outcome and rapid recovery. PRT appointments consist primarily of short, 10 – 20 minute out-patient visits two or three times per week at our Canine Physical Rehabilitation Therapy Center at the Animal Clinic of Billings and Animal Surgery Clinic.

Your veterinary orthopedic surgeon will recommend semi-weekly Physical Rehabilitation Therapy (PRT) appointments for your dog during the next two to four months following surgery for optimal post-surgical outcome and rapid recovery. PRT appointments consist primarily of short, 10 – 20 minute out-patient visits two or three times per week at our Canine Physical Rehabilitation Therapy Center at the Animal Clinic of Billings and Animal Surgery Clinic.

During this time, our PRT practitioners provide your dog with essential follow-up care, the opportunity to exercise without impact to their joints or risk of damaging the repaired injury on our underwater treadmill and utilizing our cold laser therapy.

Additionally, regular PRT appointments after surgery allow us to steadily evaluate and monitor your dog’s physical progress during the most critical stage of his or her recovery, so we can amend any necessary changes to your dog’s after-care requirements or home exercise plan if needed.

ACHILLES TENDON INJURIES IN DOGS

WHAT IS AN ACHILLES TENDON RUPTURE ON A DOG?

The Achilles tendon is the largest and most complex tendon in a dog’s body. The Achilles tendon connects a dog’s heal bone to the network of many calf muscles above it on the hind leg. Achilles tendon injuries vary in type and severity and may be caused by a blunt force trauma, a laceration, or degeneration over time.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN A DOG TEARS IT’S ACHILLES TENDON?

In order to fully understand what has happened to your dog if they have a ruptured or injured Achilles tendon, we must first break down the anatomy of the Achilles tendon itself. The Achilles tendon is composed of five different tendons. Of these five tendons, the two most notable are called the gastrocnemius tendon and the superficial digital flexor. The gastrocnemius tendon is the largest and most powerful of the two.

What Types of Achilles tendon ruptures or injuries occur in dogs?

Injuries to the Achilles mechanism can occur at three different levels:

- The highest level is when the attachment of the calf muscles are torn from the femur.

- The second level is where the calf muscles end and the tendon begins, in which a separation or tear can occur.

- The third and most common level of Achilles tendon injury is at the point of the hock where the gastrocnemius tendon attaches to the heel. Of course, lacerations can occur at any level.

Early or minor injuries typically produce a swelling and pain just above the point of the hock or heel bone. These are serious injuries and require treatment.

Achilles tendon ruptures are categorized into partial and complete ruptures or tears. In a partial Achilles tendon tear, just the gastrocnemius tendon is torn, but the superficial digital flexor and remaining three tendons are still intact. Dogs experiencing a partial Achilles tendon rupture will have a dropped rear hock and curl the toes of the affected limb while standing.

In a complete Achilles tendon tear, all five tendons have been torn. Dogs that have a complete rupture will have a completely dropped rear hock and appear to walk flat-footed instead of on their toes like normal.

With both partial and complete Achilles tendon ruptures, pain and swelling of the affected limp will set-in following the injury.

WHICH DOGS ARE MOST LIKELY TO RUPTURE THEIR ACHILLES TENDON?

Large breed working dogs and sporting dogs over five years of age are the most likely canine candidates to endure a ruptured Achilles tendon injury. Although any dog or cat can sustain a ruptured Achilles tendon injury, regardless of age, breed, or size, Doberman pinschers and Labrador retrievers seem to be the most notorious recipients of the injury.

What are the symptoms of a ruptured Achilles tendon in dogs?

Complete or partial Achilles tendon rupture symptoms include:

- Refusal to move or add weight to a hind leg

- Hind leg lameness

- Flat footed stance

- Toes will be curled downward

- Round, firm swelling in and around the area of injury

- Dropped rear hock

- Rear hock looks as though a walnut is embedded under the skin

How did my dog rupture / tear / injure it’s Achilles tendon?

A sudden and traumatic rupture or tearing of the Achilles tendon is the most likely reason a dog will sustain a complete rupture of it’s Achilles tendon. Achilles tendon ruptures or tears are more common that Achilles tendon injuries caused by a laceration or cutting of the tendon area. Even though the Achilles tendon is the strongest tendon in a dogs body, a rupture doesn’t necessarily need to be the result of a violent or traumatic event to take place.

Achilles tendon ruptures can occur slowly, over time even merely from overuse and stretching. Extremely active dogs can wear the tendon down, causing it to weaken and deteriorate until it eventually finally tears. Additionally, anything that causes a sudden and extreme flexion of the Achilles tendon or hock such as a bad fall can cause the tendon to rupture suddenly without warning.

If your dog appears to be hurt or if you notice your dog stops using one or both of its legs, please take your dog to the veterinarian immediately for a medical evaluation.

How are Achilles tendon ruptures diagnosed in dogs?

Veterinarians diagnose ruptured Achilles tendons injuries in several different ways. Most veterinarians will start by performing a physical exam on your dog. Radiographs or X-Rays and ultrasound are typically needed to confirm the diagnosis. X-rays will show if any bones are broken in or around the injury, and if not, provide proof the injury is limited to only soft tissue and tendon damage.

After X-Rays establish the state of your dog’s bones, an ultrasound is needed to determine which, if any, of the five tendons, are damaged. Ultrasound is a much more sensitive and aptly-tuned diagnostic tool for imaging soft tissues than radiographs and can register tendons and ligaments that X-Rays can’t detect. On the contrary, X-Rays are able to register broken bones and fractures that ultrasound can’t so both are necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

After X-Rays establish the state of your dog’s bones, an ultrasound is needed to determine which, if any, of the five tendons, are damaged. Ultrasound is a much more sensitive and aptly-tuned diagnostic tool for imaging soft tissues than radiographs and can register tendons and ligaments that X-Rays can’t detect. On the contrary, X-Rays are able to register broken bones and fractures that ultrasound can’t so both are necessary to confirm a diagnosis.

Aside from special diagnostic imaging, expect your veterinarian to conduct a series of manual tests and movements to the area in question on your dog. This helps your veterinarian determine the extent and severity of the injury quickly to get a feel for what to look for in the special diagnostic imaging tests.

Aside from special diagnostic imaging, expect your veterinarian to conduct a series of manual tests and movements to the area in question on your dog. This helps your veterinarian determine the extent and severity of the injury quickly to get a feel for what to look for in the special diagnostic imaging tests.

The most important components of the injury for the veterinarian to identify during the diagnosis include how high and low throughout the limb the injury extends, what all have been affected in the area of the injury, how severe the injury is, and finally, the best course of medical or surgical management needed to treat that specific injury on that specific dog.

One of our veterinarians will recommend routine blood work for your dog at this time as well, especially if the Achilles tendon injury is a result of trauma. This ensures there is no internal bleeding or additional health concerns, and all of your dog’s internal organs are still functioning correctly.

How does a veterinarian fix a torn achilles tendon on a dog?

Often, with complete Achilles tendon tears or injuries, surgery is the best treatment option for your dog to regain the use of his or her leg. More recently, regenerative stem cell treatment has become a significant contributor to our Achilles tendon injury treatment protocol. An Achilles tendon injury is extremely serious, and recovery from the injury takes a long time, but it is still possible and worth the effort. In fact, not only is recovery possible, the prognosis for Achilles tendon repair surgery is good when proper follow up and after care initiatives are strictly adhered to.

Depending on the type and severity of the Achilles tendon injury, the surgical approach will vary. The sooner your dog’s Achilles tendon tear/injury/rupture is addressed and repaired, the better the long-term results will be for your dog. If the tear goes un-fixed for too long, scar tissue begins to form over the injury and makes surgery significantly more difficult and possibly less successful, so time is of the essence.

Once the surgery is complete, it is imperative the dog’s affected limb remains strictly immobilized and appropriately supported. If the dog’s limb is not cared for properly during the recovery period after surgery, the Achilles tendon repair will not hold. Following surgery, expect your dog to have some type of external stabilization, such as a cast or external fixation pins, screws and other hardware to aid in constricting movement within the newly operated on limb and holding it firmly in place. The external fixators or cast will likely position the limb in a slightly extended manner yet in the weight-bearing position.

Recovery for dogs after achilles tendon surgery

The prognosis of Achilles tendon surgery is generally good. However, the outcome and success of an Achilles tendon repair surgery greatly depends on the client’s commitment and follow-through initiatives in adhering to the sometimes challenging and demanding level of aftercare needed. Achieving full recovery from an Achilles tendon rupture can be a long and slow process, both for you and your dog, but surgical success rates are generally good when after-care protocols are properly followed. Our veterinarians are here to help you through every step of achieving the most successful and favorable outcome for your dog possible, however, studies have shown that even after one year with ideal surgical management, complete pre-surgical strength of the tendon is not necessarily achieved.

The prognosis of Achilles tendon surgery is generally good. However, the outcome and success of an Achilles tendon repair surgery greatly depends on the client’s commitment and follow-through initiatives in adhering to the sometimes challenging and demanding level of aftercare needed. Achieving full recovery from an Achilles tendon rupture can be a long and slow process, both for you and your dog, but surgical success rates are generally good when after-care protocols are properly followed. Our veterinarians are here to help you through every step of achieving the most successful and favorable outcome for your dog possible, however, studies have shown that even after one year with ideal surgical management, complete pre-surgical strength of the tendon is not necessarily achieved.

If you elected for surgery, your veterinary surgeon will periodically need to monitor the tendon’s progress and state of repair throughout the recovery period with occasional ultrasound tests. In our experience, the most ideal treatment plans that optimize a dogs chances to re-gain the function and use of the affected limb after Achilles tendon surgery utilize extensive post-surgical physical rehabilitation and cold laser therapy. One of our veterinary surgeons will work with you to design the best PRT regiment for your dogs individualized home-care and after-care needs, as there are very specific range of motion exercises your dog will need to perform on a daily basis in order to maintain flexibility within the affected region during healing.

Laser therapy and low-impact exercise on our underwater treadmill can be very beneficial in achieving a full recovery. Laser therapy increases blood flow to the area which promotes healing, provides an analgesic effect, and can penetrate down deep to provide vital stimulation to each of the tendons affected and expedite healing.

Long-term prognosis remains good when all of these considerations are followed correctly. Most dogs with an Achilles tendon injury can recover enough to live a practically normal or near-normal life after surgery. If your dog is a high-performance athlete operating at a competitive level, the prognosis of returning to normal function to compete athletically is reduced. Even in the best circumstances, athletic performance at a competition level may be less likely as pain and mild dysfunctions may develop and even persist on a daily basis.

SUPERFICIAL DIGITAL FLEXOR TENDON (SDFT) INJURY AND LUXATION IN DOGS AND CATS

In dogs and cats, the superficial digital flexor tendon is one of the five tendons that make up the dog’s main Achilles tendon. The superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) forms the most external part of the Achilles tendon and then splits into separate branches for each toe. The primary functional purpose of the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) and it’s corresponding muscles is it enables the dog to flex and maneuver or wiggle its toes.

The SDFT tendon is held in place by soft tissue structures, and if those structures become damaged, it can allow the superficial digital flexor tendon to slip out of place and become luxated. The medical term used to describe a dislocation in veterinary medicine is luxate, luxation, luxated, or luxating.

When the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) is in a state of luxation, it usually luxates laterally by moving towards the outside of the dog’s leg. The most common cause of SDFT luxation and rupture in dogs is from vigorous activity and when strenuous rotational forces are applied to the tendon such as accidentally twisting the tendon to its breaking point suddenly during high-intensity sporting activities.

How can I tell if my dog has injured it’s superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT)?

The sudden onset of hind limb lameness is a common presentation of SDFT luxation or rupture. Sometimes, the dog will demonstrate alternating periods of intermittent lameness that changes back and forth between extreme and mild levels expressing a limp or lame hind limb.

Sometimes you can hear an occasional popping sound each time the tendon luxates or dislocates. Swelling over the point of the hock (the bump that looks like the tip of your elbow located between the dog’s ankle and it’s knee on the backside of its hind leg) is also common.

HOW IS SUPERFICIAL DIGITAL FLEXOR TENDON (SDFT) INJURY DIAGNOSED IN DOGS?

If your dog’s SFDT has ruptured or is in a state of luxation, your orthopedic surgeon should be able to feel it pop just by flexing and extending the dog’s leg with his hand on the dog’s hock. Often times, swelling over the Achilles tendon is present and offers a visual indication of what’s likely to have happened.

X-Rays will still be needed however to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the possibility of contributing fractures, bone fragmentation or any number of other problems that could also be occurring within the bones, tendons, muscles and other ligaments of the dog’s leg. If further tissue damage is suspected, an ultrasound may also be necessary to assess if additional damage to other tendons, ligaments, or cartilage has occurred.

WHAT IS THE RECOMMENDED TREATMENT FOR A DOG WITH A SUPERFICIAL DIGITAL FLEXOR TENDON (SDFT) INJURY?

Surgical repair is required for tears, ruptures, and luxation of the superficial digital flexor tendon. In a SDFT repair surgery, your veterinary surgeon will make an incision along the opposite side of the hock to which the SDFT is luxating. Then whatever fibrous tissue is damaged and no longer useful is removed.

The tendon is then reduced and moved back into place, and it’s normal position. Sutures are strategically placed inside to re-connect the tendon to its correct attachments that tore away from it. If there is limited soft tissue for the tendon to be reattached, it may be necessary to use screws or bone tunnels to make the attachment. Finally, the SDFT is reduced and stabilized into place by internally fixating non-absorbable monofilament sutures that connect the edge of the tendon to it’s originally adjoining tissues.

Post‐Operative care and physical Rehab for dogs after Superficial Digital Flexor tendon (SDFT) repair surgery

Your dog’s lower limb will likely be supported by some sort of external side splint with the tarsus (toes) fixed in a slightly flexed position for the next 6‐8 weeks. Strict exercise restrictions are required while the recovering dog or cat is in a splint and for two weeks after splint removal. Pain management is provided as needed, and a prognosis for normal function and a full recovery can be routinely expected.

BICEPS TENDON INJURY AND RUPTURE IN DOGS

What is a biceps tendon injury in dogs?

A biceps tendon injury in a dog or biceps tenosynovitis occurs when a dog’s tendon of the biceps brachia muscle and its sheath becomes damaged or inflamed. The biceps tendon attaches to the scapula (shoulder blades) and crosses over the shoulder joint, and eventually widens to become the biceps muscle. The biceps tendon is essential in stabilizing the shoulder joint, and the biceps muscle it attaches to control the functions that allow a dog to flex and extend their elbow and shoulder.

Problems affecting the biceps tendon of dogs have been reported as a frequent cause of forelimb lameness.

Some of the common conditions recognized in affecting the biceps tendon of dogs include:

- tendinopathy – a chronic change to the tendon due to repetitive injury with lack of inflammation

- tendinitis – injury with associated inflammation

- tenosynovitis – injury of the tendon and associated synovium in the shoulder joint inflammation

- partial or complete rupture of the biceps tendon

WHICH DOG BREEDS ARE MOST LIKELY TO GET BICEPS TENOSYNOVITIS?

Medium to large breed dogs in adulthood are most commonly affected by biceps tenosynovitis injuries with Labrador Retrievers and Rottweilers reporting the highest number of incidents among breeds.

Medium to large breed dogs in adulthood are most commonly affected by biceps tenosynovitis injuries with Labrador Retrievers and Rottweilers reporting the highest number of incidents among breeds.

In our area of Montana, popular hunting breads such as German Shorthairs and German Wirehairs are also commonly affected by this disorder.

Additionally, athletic dogs such as racing Greyhounds and agility dogs are also commonly affected by biceps tenosynovitis because the conditions of the injury are caused by aggressive strain and repetitive injury to the biceps tendon.

How can I tell if my dog has biceps tenosynovitis?

The most common sign a dog with biceps tenosynovitis will present is forelimb lameness. The lameness can be continuous or sporadic, and will typically become worse when the dog is allowed to exercise. Pain within the shoulder and elbow brought on by just touching the tendon near your dog’s shoulder joint may be evident.

Your dog will still be able to bear its weight on the affected limb, but he or she will demonstrate a noticeable change in stride when they walk. Look for signs of muscle atrophy (shrinking) in the affected limb as this can be a common indication that biceps tenosynovitis is present in advanced cases as well.

HOW IS BICEPS TENOSYNOVITIS DIAGNOSED IN DOGS?

This can be a challenging diagnosis to make. Biceps tenosynovitis is diagnosed several different ways in dogs. Your veterinarian is likely, to begin with, a physical exam of your dog while asking you questions related to the injury to assess possible causes. Both special shoulder X-Rays and ultrasound will likely need to be performed to assess the extent of the damage and rule out potential alternative conditions or contributing factors.

This can be a challenging diagnosis to make. Biceps tenosynovitis is diagnosed several different ways in dogs. Your veterinarian is likely, to begin with, a physical exam of your dog while asking you questions related to the injury to assess possible causes. Both special shoulder X-Rays and ultrasound will likely need to be performed to assess the extent of the damage and rule out potential alternative conditions or contributing factors.

Upon obtaining the results of these tests, if the veterinarian determines the injury is chronic, radiographs will be needed to detect if mineralization of the tendon or bone spurs surrounding the tendon sheath have developed and are present. A contrast (dye) study can also be used to diagnose a tear in the ligament, and your veterinarian may request to take a sample of the joint fluid as a means of ruling out an infection.

If the biceps tenosynovitis is at the acute stage of the condition, X-Rays will not be helpful in establishing a definitive diagnosis. The only way to make a definitive diagnosis is through an exploratory arthroscopic examination, which is useful in visualizing the extent of the injury and is minimally invasive.

HOW DID MY DOG GET BICEPS TENOSYNOVITIS?

Biceps tenosynovitis is caused by repetitively impacting the biceps tendon, such as vigorously jumping over and over in the same way during high-intensity activity, or the condition can develop simply by overusing the tendon over time. Additionally, osteochondritis dissicans (OCD) is a degenerative joint disorder that’s also been linked as a source of causing biceps tenosynovitis in dogs.

HOW IS BICEPS TENOSYNOVITIS TREATED IN DOGS?

Biceps tenosynovitis in dogs is treatable. In acute cases without tendon tears, the condition can be successfully medically managed. Recovery is aimed to decrease inflammation within the biceps muscle and tendon, so confining the patient to a state of rest with limited movement is essential.

Often times, dogs with biceps tenosynovitis are prescribed non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs or NSAIDs, and in chronic cases, corticosteroids will be injected into the joint until the desired outcome of the patient’s condition is achieved. In both instances of chronic or acute biceps tenosynovitis, the affected dog must remain under strict activity restriction for 4-6 weeks. Implementing a controlled physical therapy program once the initial resting period has been achieved is also beneficial, along with weight loss.

For dogs that do not respond to non-surgical medical treatment, surgery may be warranted. The surgical procedure to treat biceps tenosynovitis involves severing the biceps tendon from it’s scapular attachment. This is why surgery is sometimes considered a last resort form of treatment.

For dogs that do not respond to non-surgical medical treatment, surgery may be warranted. The surgical procedure to treat biceps tenosynovitis involves severing the biceps tendon from it’s scapular attachment. This is why surgery is sometimes considered a last resort form of treatment.

In some cases, a veterinary surgeon will reattach the biceps tendon to the humerus with a bone screw. Another method is to not reattach the tendon to the humorous, but rather allow the tendon to heal naturally and gradually adheres to the humerus. In both surgical procedures, the prognosis is very good, and normal muscle function is restored to the dog with time.

How can I prevent my dog from getting biceps tenosynovitis?

The best way to prevent biceps tenosynovitis is to avoid allowing your dog to overuse the limb to the point of causing damage. Dogs that participate in agility-based or high-intensity physical activities need to be properly conditioned to not over-exert or strain themselves during activity.

The best way to prevent biceps tenosynovitis is to avoid allowing your dog to overuse the limb to the point of causing damage. Dogs that participate in agility-based or high-intensity physical activities need to be properly conditioned to not over-exert or strain themselves during activity.

As with any orthopedic condition, the chances of contracting biceps tenosynovitis can be significantly decreased with proper weight management strategies.

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSIS FOR DOG’S WITH BICEPS TENOSYNOVITIS?

Non-surgical medical management methods for dogs with biceps tenosynovitis have about a 50% success rate. In most cases, dogs undergoing non-surgical treatment will need to be re-treated at least once, typically with additional NSAIDs or cortisone injections.

With surgical treatment, the prognosis is excellent, providing the patient with pain relief and resolution of lameness. Full recovery takes about 4-6 months.

Let our highly trained and experienced team of veterinarians and veterinary technicians help you keep your pet as happy and healthy as they can be.

Call the Animal Clinic of Billings to schedule your pets next wellness examination today!

406-252-9499 REQUEST AN APPOINTMENT